"Since bright the Druid's altars blazed,

And lurid shadows shed

On Almas Cliff and Brandrith Rocks,

Where human victims bled "

(Parkinson, 1882)

Brandrith Crags are located on Hall Moor, 1 mile to the north-west of Blubberhouses, on the Harrogate to Skipton road (A59).

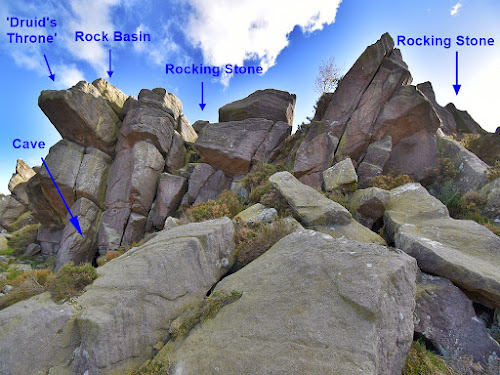

The crags are split into 3 groups, and form an east-west line across the highest part of the moor. The eastern most group is the largest, and it is here that the modern OS map marks a rocking stone. Unfortunately, the map does not pinpoint the exact location of the rock on the crag, and it appears that people have searched for it without success. This suggests that the rocking stone either no longer exists or that it is not very prominent.

There seems to be no record of the Brandrith rocking stone in recent

times, with the original reference to it dating back to the late 1700's. The

stone is mentioned in a letter which appeared in the May edition of the

Gentleman's Magazine for the year 1785 (thanks to Rhiannon at the Modern

Antiquarian website for highlighting this reference). The letter was submitted

by a "E.H." of Knaresborough - most likely Ely Hargrove, who published several

guide books for this area. The letter refers to Brandrith Crags, and notes

that ....

"Hearing some time ago the above mentioned appellation given to a ridge of rocks, situated on a mountain overlooking a deep vale, about half way betwixt Knaresbrough and Skipton, I was led to suppose the place had once been appropriated to Druidical superstition, its name manifestly implying the FIRE CIRCLE.

On coming to the place, I found it answer every description my ideas had formed of it. On the highest part of one of these rocks is a smooth, regular, well-wrought bason, formed out of the solid stone, two feet in depth, and three feet and a half in diameter. On each side of this is a smaller bason formed, each on a prominent point of the rock. A few yards from hence is a ROCKING STONE, the irregularity of the figure making it difficult to ascertain the weight exactly; yet it may be reasonably supposed to weigh near twenty tons, and so equally poised, as to be moved with ease by one hand."

Although the modern OS map does not mark the position of the rocking stone, the 1854 first edition map does show a dot on the crag for its location. The original OS map makers also drew quite an accurate outline of the crags, so by overlaying this map onto a Google satellite image of the crags it is possible to identify the particular section where they marked the stone.

|

| The 3 ton rocking stone (SE 15268 56279) |

A search along the top of the crag found no obvious signs of a

large rocking stone. All the rock appears to be either part of the outcrop, or

boulders firmly settled in position. A closer inspection was then made of the

area indicated on the old OS map, and here, after some searching, a stone

block was noted resting on a curved undersurface. Pushing the stone had no

effect, but standing on one end of it did make it move. Was this Hargrove's

rocking stone? The boulder is certainly 'irregular' in shape, and it is

located a 'few yards' from a large rock basin, which appears to be the one

described in Hargrove's letter. However, this stone cannot be rocked by hand,

and its size (around 3 tons) does not tally with Hargrove's estimation of its

weight at 20 tons.

|

| The 20 ton rocking stone (SE 15254 56275) |

The uncertainty around the rocking stone prompted a second

visit to Hall Moor, and a closer look at the rocks along the crags. This time

a larger boulder was found, which can be moved by hand, it is also irregular

in shape, and its size indicates a weight around the 20 ton mark. This rock

sits on a narrow section of its base, which provides a single pivot point, and

means that it can be rocked by pushing the projecting end of the rock. These

details, along with the stones position only 15 yards or so from the basin

rock, would seem to fit with Hargrove's description.

Both the 3 ton and 20 ton rocking stones found on the crag can be easily missed, as they are not of the 'classic type', where a large boulder is raised up on top of a flat lower rock - like the one at Rocking Hall on the moors further north. Both rocks sit amongst other large boulders on the crag, and this might explain why Hargrove's is the only reference to a rocking stone here, and why people have been unable to find it in more recent times. The local historian William Grainge visited Brandrith Crags in the mid 1800's, and described the 'Druidic' rock basins in some detail, but he makes no mention of a rocking stone. This again suggests that Hargrove's stone was not a prominent feature, and was easily missed. It is likely that the rocking stones were known about locally, but this would depend on someone being present on the moor to point them out to visitors.

Mark yon altar.

Those mighty piles of magic planted rock,

Thus ranged in mystic order : mark the place,

Where, but at times of solemn festival

The Druid leads his train. There dwells the seer

In yonder shaggy cave, on which the moon

Now sheds a side-long gleam ; his brotherhood

Possess the neighbouring cliffs :

Mine eye descries a distant range of caves,

Delved in the ridges of the craggy steep.”

(Hargrove 1789)

During the 18th century there was a renewed interest in the ancient Druids, which led to them being associated with stone circles and other unusual rock features. Signs of fire or burning, along with eroded basins and snaking channels found on top of outcrops and boulders were seen as evidence of their ritual sites. From Hargrove's letter it is clear that he visited Brandrith Crags with 'Druidical expectations', hoping to find signs that the crags had been used by the Druids. He found the large rock cut basin, and a boulder stone nearby that could be rocked by hand, which convinced him enough that Brand-rith had been the "Fire circle" of the Druids.

When viewed across the moors from the south, the crags appear as a low ridge of jumbled rocks. However, from the lower ground to the north, the crags present a high rock face with overhanging blocks of stone. At the foot of the crags, below the basin and the 3 ton rocking stone, there is a small cave or rock shelter, which Hargrove must not have seen during his visit, or he would have surely included it as another Druidic feature.

A fellow Druidophile - David Lewis of York, wrote a poem after he

visited Brandrith Crags in the early 1800's. The poem starts with the lines

.....

Over Kexgill heaving high,

Brandrith fronts the polar sky;

On the

mountain's topmost stone

I descry the Druid's throne,

Nicely poised

in the air;

Soon I gain the vacant chair:

To that seat's commodious

form,

Sculptured by the mountain's storm,

|

|

The 'Druid's Throne' Rock basin |

The 'Druid's Throne' seems to be a poetic fancy, but it does sound

like Lewis sat on the highest part of the crag. Checking the basin rock again

during the second visit to the crags, found that it does actually have a throne

like appearance. When the basin is dry it would be possible to sit in it (bring

a big Druidic cushion), or perch in the gap on the far side, with feet

resting on the ledge below. This would seem to be the inspiration for the 'Druid's Throne', and from this lofty viewpoint, the rolling landscape can

be surveyed stretching away to the north and west.

The crags associations with druids originated in the Romanticism of the 18th century. However, it is worth noting that when viewed from Brandrith Crags, the rocking stone at Rocking Hall would be visible on the skyline to the north-west (this is before the shooting house was built in front of it). Also visible on the nearby moor is the Raven Stones prehistoric rock art site. Further north on the horizon stand the huge outcrops at Simon's Seat, along with the Great Pock Stones, and the hills at Greenhow.

|

|

Location of the two rocking stones and the basin stone (red triangles) view from south |

After thoughts

A Brandrith was originally a metal tripod used to supend a gridle plate over a fire. The word was later used to descibe a point where 3 parishes met, so in this case the '3' element may refer to the 3 outcrops on the moor which make up Brandrith crags.

Also worth noting that the French name for a rocking stone is Pierre Branlante, branlant meaning to wobble, shake or rock, and possibly connected with the word brandish through a Germanic/Norse root word.

References

Hargrove, E. (1785) Letter in the Gentleman's Magazine for 1785, pt.1, p360

Hargrove E. (1789) The History of the Castle, Town, and Forest of Knaresborough.

Lewis, D. (1815) The Landscape, and Other Poems.

Parkinson, T. (1882) Lays and Leaves of the Forest.

Post a Comment